Let’s Power Glendale with Clean Energy!

Join Glendale’s Virtual Power Plant & BE PART OF THE CLEAN ENERGY SOLUTION!

Clean Energy Solutions for Glendale That Could Save You Money

. . . and ensure backup power to keep your own critical appliances running in the case of an outage!

Glendale is on the cusp of adopting a Virtual Power Plant that will be the LARGEST of its kind in the ENTIRE COUNTRY. You can be part of this historic clean energy project! The term “People Powering Glendale” is exactly what this is. YOU can be part of our energy solution, and help us avoid new gas capacity at Grayson, by allowing your building or home to house solar and battery storage while providing critical, clean, local energy to our city grid when it is needed most, day or night.

From our current understanding of the program, for single-family homes, the owner receives a monthly payment applied to their utility bill plus backup power from the battery during any outages. Multi-family buildings (including apartment buildings, condos, retirement homes) will have customized agreements based on system sizes and battery capacity, and will also have critical battery backup. How great would this be for your home or building?!

On October 13, 2020, Glendale City Council approved GWP to complete negotiations with SunRun. If the negotiations conclude successfully, the Virtual Power Plant should begin implementation in January, 2021. When the final details are worked out and publicly shareable, we will post them! If you happen to know of building owners (apartment buildings, condos, eldercare facilities, and retirement communities), please send us the owner’s contact info so we can pass that information along (contact@gec.eco) or have them add their contact info to our interest form below. We are keeping track so that you can be apprised of the program when it begins! Thank you to the over 375 people who have expressed an interest thus far!

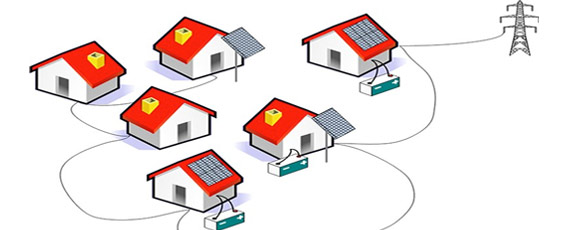

A VIRTUAL POWER PLANT is a creative alternative to centralized power-generating plants. It’s a cluster of individual sites (such as homes)—each with solar panels and a high-capacity battery—networked together.

The utility subsidizes the cost of the battery and/or the solar panels, and in return, the property owner agrees to let the utility tap into the energy stored in the battery when demand peaks. The property owner keeps a guaranteed minimum of backup power to run critical things like the fridge and lights.

Instead of building a gas “peaker” unit just for infrequent peak-demand episodes, or paying exorbitant amounts of money to bring in outside power, the city can turn to its own residents. We’d have a local clean-energy power bank, and a more reliable and resilient system!

YES! I want to receive information about how I can participate in the virtual power plant by adopting a home solar and smart battery system while receiving backup power during outages, reducing my energy costs with a monthly payment for participating and helping eliminate the need for a polluting power plant in Glendale.

WHY are we asking you to add your information below? It allows us to keep you informed as this exciting project moves forward.

The Glendale Environmental Coalition will use your information SOLELY for the purposes of a virtual power plant. There is no obligation to participate. We will NOT sell or rent or otherwise use your information, and we will delete your information upon your request. You can contact us here with any questions. Thank you!

Who can be a part of a VPP?

Anyone in Glendale, Montrose, or La Crescenta (if you are a GWP customer). Even if you don’t already have solar panels on your roof, there are ways to have them installed and get a high efficiency battery for your home with long-term financing at a cost that’s less than what you’re currently paying to GWP for power. And the more people who join the VPP, the cheaper the rate for everyone.

How can you get updates on the VPP’s progress?

By submitting the form above. You will receive an update once the program structure and terms have been worked out with GWP.

If you submit your name on the VPP Initiative, are you obligated in any way?

No. You’re not committed to anything, except learning more! This information will be used as background data to help our solar partners work out the program with GWP and advance support by City Council for clean-energy alternatives in Glendale. You may be contacted by us or one of our solar partners down the line to update you on negotiated rates under the new VPP plan, but it will be “light touch” and you will not be contacted by multiple parties. The more people who fill out this form to show their support, the lower the rate our solar partners will be able to negotiate with GWP for your cost savings down the line.

I have a Spanish tile roof. Can I still install solar?

We understand that there’s at least one company working in the area that can do Spanish tiles. We don’t know how tricky it is, but we’re definitely going to be looking into it because there are a lot of tile roofs around Glendale. We’ll let folks in this situation know what we find when we’re closer to rolling out the program.

I already have solar installed. Can I still participate?

Our hope and expectation is that this program can integrate multiple solar systems so there is space for a variety of installers to compete and/or people with existing systems to participate. The key will be getting the various systems to interconnect with the batteries, and getting the batteries on a single software platform so they can be managed centrally.

We have been looking into solar and have a proposal we are considering.

We are hoping and expecting that the VPP will be designed to integrate solar systems from different providers. Getting the batteries to talk to one another using a centrally managed software platform will be the key.

We have solar panels, and are interested in a battery. Will the system operate during blackouts?

We intend for the project to be designed so that residents have at least 20–30% of the battery capacity available at all times in the event of a blackout. This would allow for about 7 hours of continuous use for basic services like lights, fridge, and fans. (It would not be enough for full-blast A/C for 7 hours, though). If the blackout runs over into the next day, the battery could charge from the solar and then be available for additional use.

Would having a battery through the VPP be less expensive than just purchasing it myself?

As far as affordability goes, the key to this is getting GWP to pay for a substantial part of the battery cost in exchange for access to the power during a heat emergency when demand spikes.

I have lots of shade trees on my property; not sure if solar panels would be practical for my house.

The short answer is that we won’t know until we get someone to do a roof analysis. A rough analysis can be done remotely using satellite data, or a somewhat more accurate one by having someone actually go on the roof and do a shade study (the companies don’t charge for this, by the way, so don’t pay anything to anyone for it!). If you can hang on for a few months while we get the project details worked out with GWP, we can get someone to take a look and see whether it will work for you.

We do not have solar, but have had an interest for quite a while. Main reason for not having done it yet was upfront cost.

We are hoping to be able to address the upfront cost issue by having a few different financing options available. Not all solar installers offer financing, but some do, and we’re working with one that has a strong lease program. You don’t pay anything up front, but just make monthly payments over 20 years. We’re going to be working out details with GWP over the next few months, but the goal is that these monthly payments come in at or below what you pay today for electricity so that the solar basically pays for itself. The other good thing with this is that you are protected against rising costs from GWP, and the lease also includes 20 years of free maintenance and replacement of any parts that go bad. Please hang in there while we get things set up.

Getting a new roof next year; would that be a good time to add solar if we can afford it?

One thing to know is that if you get solar, you get a federal tax credit not only for the cost of the solar but also for the cost of the roof replacement (30% in 2019, decreasing after that). So adding solar when you replace a roof is really a smart move. It’s very likely your solar will pay for itself because of this, but we’ll only know this for sure when the program details are worked out with GWP. Since that will take several months, your timing looks perfect!

Why a VPP in Glendale?

The VPP is a terrific opportunity to:

- Reduce energy demand in Glendale; and

- Demonstrate to City Council that we do not want to further contribute to climate change or worsen our air quality by expanding the Grayson gas plant! We already have the worst ozone emissions in the nation right here in LA County. Why on earth would we make it worse in Glendale by expanding Grayson?!

The future of a larger Grayson gas plant is hanging in the balance. It’s important that Glendale residents step up and demonstrate their willingness to be part of a clean alternative to meet Glendale’s power needs.

And by participating in a Virtual Power Plant, residents can save money on their power bill! With a networked VPP, residents who participate can band together and power their homes at a lower all-in cost than they pay GWP today.

The Real-Life Distributed Storage Case Study We’ve All Been Waiting For

Green Mountain Power tested its fleet of Powerwalls against a record heatwave and crushed its annual peak.

by Julian Spector

July 30, 2018

A clean energy legend became fact, and we’re going to print the facts here.

Any energy transition enthusiast worth their value stack has recounted the theory that small-scale, distributed equipment can save a bunch of money for the bulk electricity system. With the right incentives, private capital could install equipment in customers’ homes that works together with the utility for the benefit of all.

You could argue that California’s commercial storage companies have made this happen, aggregating batteries at businesses for grid-scale capacity or demand response. And New York did something tangible for once with the Brooklyn Queens Demand Management substation upgrade deferral project.

But what about distributed energy at the smallest scale—in the home—and performing in real-world operations, not in some one-off pilot?

Now we’ve got it.

A heat wave descended on New England the week of July 4, sending electricity demand surging in the afternoons.

“You step outside and it was like stepping into mud,” recalled Josh Castonguay, VP and chief innovation executive at Green Mountain Power, Vermont’s largest utility. “When the humidity starts to ramp up, the air conditioning starts working hard.”

For the utility, that meant watching out for the New England ISO annual system peak, which sets a capacity charge that each utility in the region has to pay, proportional to their consumption during that hour. Those 60 minutes drive a considerable portion of the costs that GMP passes on to customers every year.

In the old days, utilities had to take the peaks more or less as they came. But GMP had a shiny new tool to wield: a fleet of Tesla Powerwall batteries installed in customer homes across its territory.

The heat wave, then, created one of the most robust natural experiments so far to test the efficacy of decentralized energy resources in reducing systemwide stress. Like a firefighter spraying down a burning building, GMP discharged the batteries when the peak was cresting, keeping it from rising higher.

Now the utility knows exactly how much electricity it would have consumed without the storage, and what system peak capacity charge it would have had to pay. It can compare that to its actual demand and resulting charge.

The result: at least $510,000 in savings, and an experience worth studying for anyone trying to optimize customer-sited energy tools to fight system peaks elsewhere on the grid.

The program

GMP talks a lot about serving its customers and embracing the future of distributed grids. The Powerwall program tackles both goals.

The utility began offering heavily subsidized Powerwall batteries to its residential customers in 2015, and followed up with a cheaper program in 2017 after the launch of the Powerwall 2. The homeowner can access the hot gadget for $15 a month for 10 years or $1,500 upfront, far below the (recently inflated) list price of $5,900.

It can’t do a lot for them, to be honest. With full net energy metering, Vermont residents have no economic incentive to shift around solar production or avoid consumption during peak hours.

However, they do suffer from the occasional winter storm, and the Powerwall promises clean, near-instantaneous backup power, which can recharge indefinitely when paired with rooftop solar generation.

Meanwhile, the utility gets a network of distributed batteries it can harness for capacity during monthly and annual peak events. It even got permission to rate-base the project, because it expects it to cover costs and return a significant amount of value to ratepayers overall—$2 million to $3 million in net value over 10 years.

Critics of the program have questioned the customer benefit of paying out of pocket in order to host a tool primarily for the utility to use.

GMP’s outage data shows an average customer downtime of a little over two hours per year, Castonguay told me. That means some customers could pay more than their Netflix bill each month for a battery that will never be needed. Others, in more remote, wooded areas, might pay the same and call on the backup several times a year for prolonged outages. The value varies significantly based on customer circumstances.

For a while it looked from the outside like customer skepticism won out and adoption stayed low. Lately, though, the numbers tell a different story.

The program has installed 550 Powerwall 2 units, Castonguay said, with an additional 514 contracts signed and scheduled. Two to four units get installed each day. Another 622 are somewhere in the pipeline before the signing stage, joined by 30 to 40 newcomers each week.

GMP wants to sign up 2,000 units by the end of the year; that’s out of a total customer pool of 265,000 meter locations.

“Is $15 a month going to work for folks when they think about the value of resilience?” Castonguay asked. “What we’re seeing in the rollout is that it is.”

Even getting one’s hands on that many units of the notoriously backlogged Powerwallamounts to the cleantech equivalent of parting the Red Sea. GMP initiated that relationship years ago, Castonguay said, even before the Powerwall had fully materialized as a consumer-ready product.

The program has tackled three main questions: Can the utility use the batteries to tackle peaks without causing other problems on the grid; does the battery provide a resiliency value to the host customer; and will the battery fleet reduce carbon emissions from peak capacity?

The peak approaches

Going into July, GMP’s indicators warned that a peak was coming.

When the New England ISO’s annual peak arrives, each utility in the region pays for its share of the peak demand, plus the reserve margin procured ahead of time through capacity auctions.

“Every megawatt we cut off our peak at the time is that much less that our customers have to pay into the New England capacity market,” Castonguay explained. It’s better than one-to-one savings, he added, because every megawatt consumed incurs a charge for the extra margin procured.

The utility leaped into action on Tuesday, July 3, which set a peak.

“That day we had all our systems aimed and ready to go,” Castonguay said. “We went after that one and hit it.”

On July 4, demand dropped due to the holiday. But the next day, it came back with a vengeance. Boston, a major regional load center, stayed hot. Burlington was breaking heat records.

The GMP team, watching in real time, had at its disposal nearly 3 megawatts of Powerwall capacity, plus a 1-megawatt/4-megawatt-hour Powerpack facility and the Stafford Hill battery plant.

“We started rocking and rolling around 4 p.m. with our systems,” Castonguay recalled. “We shoot at a two-to-three hour window to make sure we hit it.”

The peak arrived in the hour starting at 5 p.m.

GMP previously had been able to verify that the reliability role of the Powerwalls was working for customers, and the system had performed for monthly peaks, which drive payments to the transmission system. But this was the first time it had fired on an annual system peak.

“It was such an awesome test and proof positive of things functioning as expected,” Castonguay said. “We were able to hammer on that peak hour.”

The combined energy storage assets shaved $510,000 from the peak payment. And that was with only a small fraction of the targeted Powerwall deployment.

Yes, but does it scale?

This deployment generated a hard piece of evidence for the theory that distributed batteries can help out both host customers and the customer population at large.

Now the question is whether that success can translate to other jurisdictions.

From a technical perspective, there shouldn’t be any obstacle to implementing a similar playbook in another utility territory, Castonguay said. The trick will be tailoring the program to the economics of the new location, as governed by the value streams available in that market.

“Understanding what those are and how the batteries can capture them is going to give you a different outcome in terms of how much you’re going to collect,” he noted. “Maybe instead of $15, it has to be $20, or maybe $10 a month.”

The regulatory context will influence the design of the program. As a regulated utility, GMP needn’t worry about the competition concerns that arise when deregulated utilities try to own certain energy assets.

In New Hampshire, for instance, Liberty Utilities proposed an even more grid-edgy planwhere customers would pay monthly for a Powerwall, entering them into time-of-use rates and collectively constituting a non-wires alternative to more expensive traditional grid investments.

That proposal, though, drew opposition from other storage providers who argued it would endanger the competitive landscape to have the utility owning those assets.

Regulators in other states may want to see smaller-scale testing of the concept before signing off on larger programs. Such an attitude would no doubt be couched in caution for the prudent use of ratepayer dollars, but would only delay the cost savings that ratepayers could receive from following GMP’s lead.

Indeed, this is one of the few cases in which a utility can claim to have lived out the notion that fortune favors the bold. GMP didn’t settle for a timid 30-unit pilot, or 50.

“We’re much more focused on executing for customers, rather than studying and planning and studying in planning,” Castonguay said. “Can you produce the value or not?”

Even just a quarter way to its current 2,000-unit goal, the utility saved several hundred thousand dollars in one hour. That leaves one to wonder what could happen with thousands of home batteries ready to rock and roll.

Discover more from Glendale Environmental Coalition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.